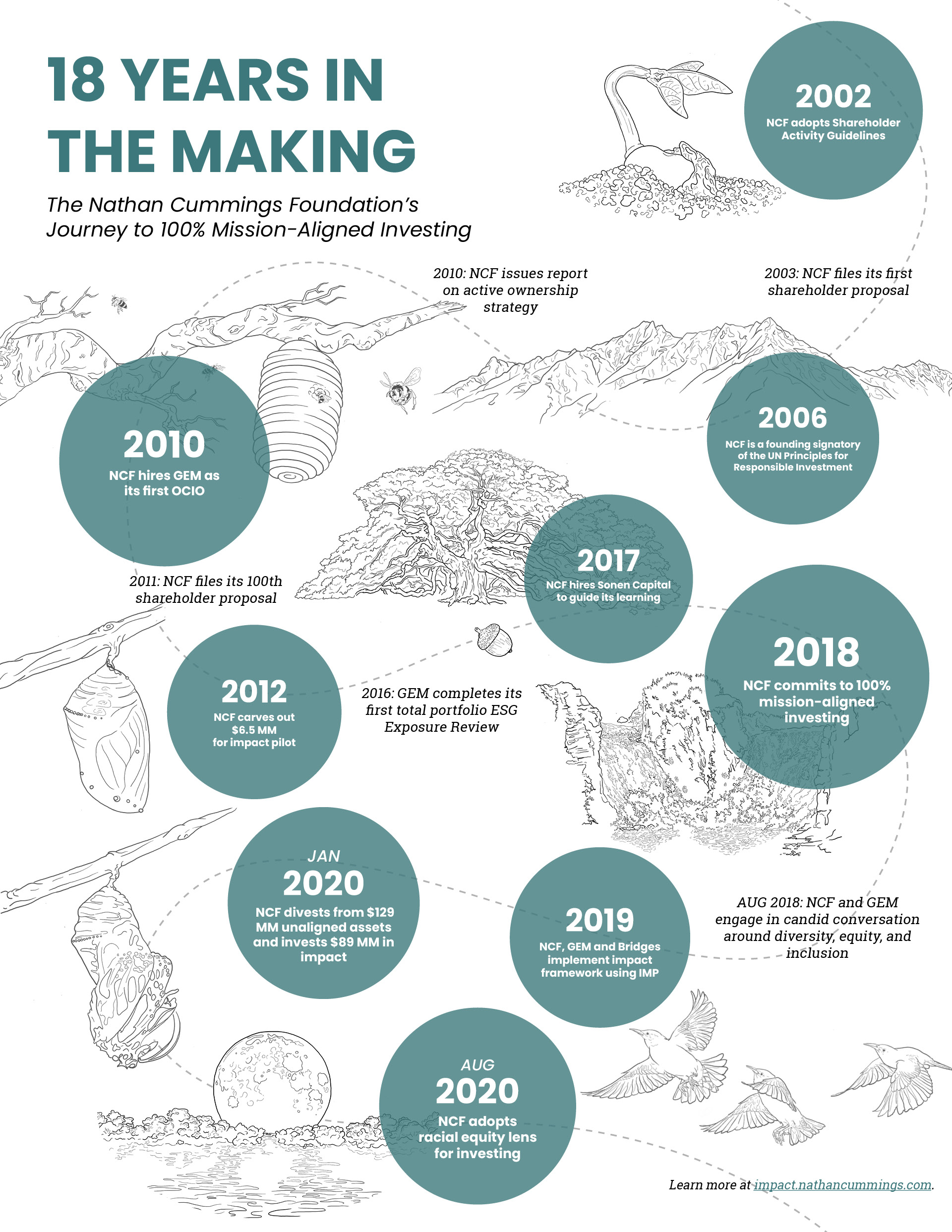

On November 12, 2017, the trustees of the Nathan Cummings Foundation filed into the 14th floor Board room of the foundation’s Midtown Manhattan headquarters. It was a crisp, glorious Sunday, but none of the trustees resented being stuck inside on the weekend because this was no ordinary Board meeting. The trustees would be making the foundation’s biggest, most consequential decision in decades, the culmination of fourteen years of learning and intense debate. “Our CEO at the time cared so deeply about the outcome that she was placing calls to trustees until the eleventh hour,” recalls Jaimie Mayer, current Board chair. “The future of the foundation was riding on this decision.”

The issue on the table: should the foundation use its $450 million endowment, not just its $20 million in annual grants, to advance the foundation’s social mission?

“Today, we have an opportunity to go to a place we don’t know, for the benefit of the foundation’s mission.”

The Board room was packed. In addition to ten trustees from the Cummings family and four independent trustees, the group included one associate (a fourth-generation Cummings family member in training for a future governance role), two professional advisors to the Board’s Investment Committee, fifteen staff members, and seven guests with expertise in impact investing. Then-chair Ruth Cummings, who had flown in from Jerusalem for the meeting, sat a few paces from a bronze bust of her paternal grandfather, the foundation’s namesake. After bringing the meeting to order, she shared a few thoughts about the serendipitous relevance of the week’s Torah (Hebrew Bible) portion.

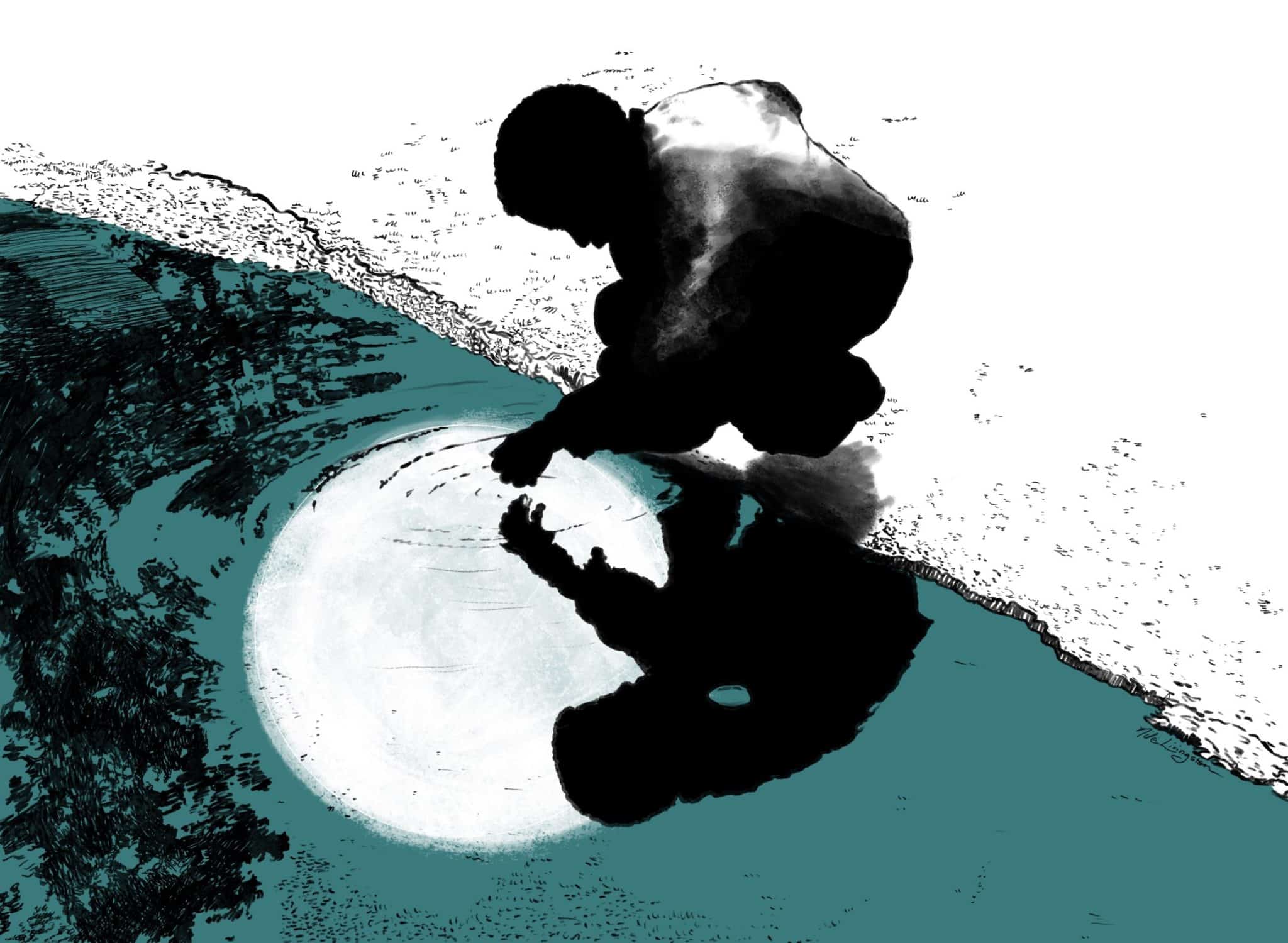

Respecting the fact that fewer than half of the attendees were Jewish, Ruth explained that the Torah portion corresponding to that week was called Lech Lecha, a Hebrew phrase that means “go to the place that is your own” or “go to your self.” She shared that this portion discussed the story of Abraham — the patriarch of Judaism, Islam, and Christianity — and his courageous decision to leave his father’s house and native land to begin anew in the land of Canaan. She told the trustees that they, too, could break from tradition and seek courageous transformation. “Today, we have an opportunity to go to a place we don’t know, for the benefit of the foundation’s mission,” she said. “We can embrace a new investment model, and if we’re successful, we will lead the way for other foundations, including those with much greater resources. The stakes are high.”

Ruth was unambiguous about her desire to go all in on impact investment. But a “yes” vote was no foregone conclusion. No foundation of Nathan Cummings’ size had done so. Several of the foundation’s Investment Committee members, to whom the Board had traditionally delegated all key endowment decisions, were not ready to take a leap of faith. While she felt she had a pretty good read on how her family members would vote, she was not as clear about where the foundation’s four independent trustees stood.

The two co-chairs of the Board’s Investment Committee, Ruth’s cousin James K. Cummings and independent committee member John Levy, had a good working relationship but did not always see eye-to-eye on impact investment. James, who had lived on a commune in the 1960s and still wears an earring in his left ear, was the number one champion of aligning investments with the mission. He had been bringing up the topic since the 1980s when his father was the foundation’s president. “He was polite, an impeccable person,” James explains. “And he made it emphatically clear that we were not going to have that Board-level discussion.”

Levy, a New York tech venture capitalist with experience in early-stage social enterprise investing, approached impact investment “with a healthy dose of skepticism,” in his words. Although he believed that aligning investments with the mission would be desirable, he was worried that it wasn’t feasible — at least not with the market-rate financial returns the foundation needed to maintain its grant budget and pay its talented staff of nineteen professionals. “We can’t do anything good unless we have money coming in,” Levy told James at one point. “If we don’t have strong returns and sufficient liquidity to pay for operations and grants, then all the other tools become unavailable.”

Despite the differing perspectives, when Ruth kicked off the Board’s impact investment discussion, it felt to her like she was pushing on an open door. One big factor was that Levy had flipped to the “pro” side. He explained that he had recently concluded that Global Endowment Management (GEM), the firm that managed the foundation’s investments, would put the necessary resources into building its own capacity to deliver both social impact and competitive financial returns using the same infrastructure and processes that enabled them to be so successful for the foundation in the past. “John was the big wild card going into that meeting,” Mayer reported later. “John’s mindset shift was critical for me.”

Two other issues played a significant role. While the name Donald Trump never came up in the discussion, several trustees felt a great urgency to give the foundation new tools to address issues like racial equity and climate change in light of the ways the new Administration was undermining progress. In addition, the trustees had engaged together in an intensive learning process that was conducted by San Francisco–based Sonen Capital. The trustees had nothing but praise for the nine-month process. It had given them ample opportunity to meet with experts, ask lots of questions, and assuage concerns.

Ruth’s passionate and outspoken brother, Adam Cummings, made a plea for the foundation to “develop our risk-taking muscles” and “use our privilege to make as much of a difference as we can.” The Board voted to approve a proposed investment values statement focused on aligning investments with the mission. The vote was unanimous.

Then came the real moment of truth. Ruth raised a motion to move 100 percent of the foundation’s endowment into investments aligned with the foundation’s mission, with a first step of moving approximately 20 percent ($100 million). The entire Board voted in favor. “Going into the meeting, I thought that if we could agree to move 50 percent into impact investments, that would be amazing,” Mayer said. “It never even occurred to me that we could end up at 100 percent, let alone a unanimous decision to go there. I was shell-shocked.”

“It never even occurred to me that we could end up at 100 percent, let alone a unanimous decision to go there.”

Rick Cummings, James’ brother, made a point of publicly acknowledging James for his persistence and leadership. “This is something that James has been pushing for and lobbying for quite a good number of years,” he said. “How perfect to vote to do this within days of his 70th birthday. It’s a fitting way to honor James’ commitment to helping heal the world.”

A Toe in the Water

The foundation’s first foray into using its whole endowment, not just its grants, to make change came over a decade earlier, in the form of shareholder engagement.

When Lance Lindblom, a progressive lawyer with decades of policy and foundation experience, interviewed for the role of foundation president and CEO, he shared his view that the foundation was missing a big opportunity by using only its grant budget — typically 5 percent of its assets — to affect change; it was failing to leverage the other 95 percent. He argued that the foundation could punch above its weight by being an active investor, without spending additional money on grants and with only modest administrative costs. This active-investor strategy would mean filing proposals at publicly traded companies whose shares it owned and voting on these and other proposals relevant to the foundation’s mission. He told the trustees he was surprised and a bit dismayed that very few foundations were using this point of leverage, given that foundations are among the largest shareholders in the US.

The Board, which had already begun discussions about voting its values, liked what Lindblom was proposing, and they hired him. Less than two years later, the Board adopted a set of guidelines specifying how it would begin to engage with public companies in which it invested. Shareholder activism quickly became a central component of the foundation’s work and self-identity. “It’s now one of the most powerful tools we have,” according to Ruth Cummings.

To date, the foundation has filed more than 225 proposals for inclusion in corporations’ proxy statements, often in close collaboration with its grantees. The foundation also votes its values on others’ proposals. In 2020 alone, it cast more than 6,500 proxy votes.

Although the foundation has succeeded only a handful of times in getting a majority of shareholders to approve its proposals, it has discovered that having a positive influence does not require outright wins. The foundation has scored numerous victories simply by filing motions that generate interest from other shareholders and the press, because that often brings the corporation’s senior leadership to the negotiation table.

In 2003, the foundation led its first shareholder action, a proposal it filed with Smithfield Foods. Smithfield Foods was a large and successful food-processor, like the company Nathan Cummings founded in the same era. The foundation’s resolution focused on getting Smithfield to measure and report on its environmental impacts, an issue several of the foundation’s grantees had tried unsuccessfully to get Smithfield to address. Although the Security and Exchange Commission rejected the resolution on technical grounds, it gave the foundation entrée to the company’s vice president for environmental and corporate affairs and its chief legal officer, who flew to New York to meet with Lindblom, his colleague Laura Campos, and executives from several other foundations. The negotiations yielded concrete results. A National Research Council report later concluded that the foundation “caused Smithfield to critically examine its own reporting and how its supply chain is reviewed…The expectation by all parties is that increased transparency will support continuous improvement and sustainable environmental outcomes in Smithfield Foods’ operations.”

“Shareholder activism quickly became a central component of the foundation’s work and self-identity.”

In the subsequent seventeen years, the foundation scored many David-versus-Goliath wins. For example, it used its voice and votes to get Apple, UnitedHealth Group, and other huge companies to implement “say-on-pay” provisions, giving investors the ability to influence the companies’ executive-compensation policies, a key driver of income inequality. This say-on-pay advocacy was so successful that it’s no longer necessary; it was made mandatory for all United States publicly traded companies under the Dodd-Frank Act passed in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis. It successfully pushed Walmart to use more effective supply-chain screens to identify suppliers that use diversion programs or prison labor. Its first attempt to affect corporate behavior on climate change was so successful that its target, Valero Energy, committed to carbon-reduction measures that went beyond what the foundation was requesting. The foundation won significant commitments from some of the nation’s largest homebuilders, reducing carbon dioxide emissions by thousands of tons each year. In 2017, the foundation and Wespath, the investment arm of the United Methodist Church, spearheaded the first oil-and-gas resolution in US history that earned a majority vote — thanks in great measure to the fact that it won the support of mega-investors Blackrock and Vanguard.

For a decade now, the foundation’s executives and trustees have been making the case that “the way in which a company approaches major public policy issues has important implications for long-term shareholder value,” in the words of its report Changing Corporate Behavior Through Activism. To their delight, many other influential players have joined the choir. “In the past five years, we’ve benefitted from a real sea change in attitudes in the investor community,” says Campos, who now serves as director of the foundation’s corporate and political accountability program. “I can’t point to one thing that produced the change. It’s been the culmination of many years of efforts. Investors are now able to build air-tight cases that environmental and social issues have an impact on companies’ bottom line, just as much as governance does.”

Impact Investment, Silo Style

The trustees decided to create a new Assets Aligned for Impact Committee in 2012 to build on the foundation’s shareholder activism. James Cummings was the natural choice to lead the new committee, given his many years of advocacy. “For a long time, I wanted to bridge the divide between the investment team and the program team. I didn’t have a bunch of letters after my name, so I didn’t feel comfortable pushing too hard. The new committee gave me the right platform to explore what more we could do,” he says.

The trustees decided to create a new Assets Aligned for Impact Committee in 2012 to build on the foundation’s shareholder activism. James Cummings was the natural choice to lead the new committee, given his many years of advocacy. “For a long time, I wanted to bridge the divide between the investment team and the program team. I didn’t have a bunch of letters after my name, so I didn’t feel comfortable pushing too hard. The new committee gave me the right platform to explore what more we could do,” he says.

The foundation had been screening out tobacco and weapons companies from its portfolio since the early 1990s. Several trustees felt it was time to dive into impact investment. “That was a no-brainer for me,” Ruth Cummings recalls. “I said, ‘Let’s do it!’”

Other trustees, and most of the external advisors who served on the foundation’s Investment Committee, were skittish. Myra Drucker, a respected pension fund administrator who chaired the Investment Committee at the time, felt that the impact investment field was in an early stage, with limited deal flow. She also didn’t want to hamstring the foundation’s investment managers, who already faced the challenge of earning steady returns to fund the foundation’s programs while keeping financial risks to a minimum.

Nonetheless, the new Assets Aligned for Impact Committee convinced the trustees to earmark $6.5 million, about 1.5 percent of the endowment, for impact investments, starting in 2013. The decision marked a major break from the Board’s tradition of deferring to the outside experts on its Investment Committee on all matters related to the foundation’s portfolio.

The trustees agreed that no single impact investment would be greater than $250,000 or longer in term than six months to assuage fears about straying from the foundation’s traditional approach to endowment management. They also agreed that they would choose investments that had limited downside risk, focusing primarily on investments in credit unions, community banks, and loan pools for low-income homebuyers. According to James, “We agreed that we would make very safe investments initially. That was important for the Board. That was certainly important for the Investment Committee.”

Over the next three years, the foundation deployed roughly $4.5 million in new impact investments, which eventually included some with longer terms or higher risk, like private equity. These investments generally outperformed their benchmarks and returned about 4 percent annually. Yet, today the trustees do not look back at the experiment as a clear success. With twenty-twenty hindsight, it’s easy to see that the trustees made three missteps.

- First, they didn’t create enough internal transparency. The Board and staff had little opportunity to learn what worked and what did not, because the impact investment portfolio was so siloed. Even the Investment Committee was in the dark. “When I began as chair of the Investment Committee, I didn’t know anything about the impact investment portfolio,” John Levy says. The only entities with visibility were the Assets Aligned for Impact Committee and its investment advisor, Imprint Capital Advisors.

- Second, “the money could have been put to work more quickly,” James acknowledges. “With a slower-than-anticipated pace, these early investments did not pique people’s interest as they could have.”

- Finally, the foundation put no metrics in place to measure the social impact of these early investments. In the words of former trustee and Board treasurer Michael Cummings, “There was never any evidence presented or shared about whether or not these investments were working or providing actual impact.”

A Year of Learning Intentionally

Once it became clear that the siloed approach to impact investment was not ideal, the Board decided to test the feasibility and desirability of a fully integrated approach. In early 2017, the foundation’s then-president and CEO Sharon Alpert sent out a request for proposals to help her and the Board select a firm to guide an intensive learning process. She and the Board selected Sonen Capital. Although Sonen’s main line of business was managing impact investments, their expertise and sensibilities were just right for the foundation’s needs. “Sharon brought new voices and perspectives to our table,” reflects Rey Ramsey, one of the foundation’s independent trustees. “It was critical to our process.”

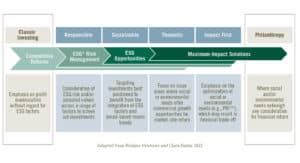

In April 2017, Sonen founder Raúl Pomares met with the Board in a small conference room to share an overview of the impact investment field. He started by aligning the group around a common definition of impact investment: “The full range of investment opportunities which address an investor’s desire to realize financial return while achieving meaningful and measurable positive social and/or environmental impact.” His definition embraced a broad spectrum of approaches, ranging from basic ESG screens to targeted, “impact-first” opportunities.

A slide from Sonen’s April 2017 presentation to the foundation’s Board and staff.

Financial returns were top-of-mind for every trustee. Would the foundation have to sacrifice returns if it were to commit to make impact investment a core component of its portfolio? If so, how much of a “haircut” might they have to take? What would be the implications for the foundation’s grantmaking?

To the surprise of most Board and staff members, Pomares told them that they wouldn’t have to sacrifice returns. He then projected a chart showing that each asset class in the foundation’s existing portfolio — cash, fixed income, public equity, private equity, hedge funds, real estate, and commodities — had mission-aligned analogs that were likely to produce equivalent returns.

During May and June, Sonen conducted in-person and phone interviews with twenty-five of the foundation’s trustees, associates, independent Investment Committee members, staff, and outside investment managers. The interviewees offered many probing questions about risks, cost, and operational implications. Most interviewees expressed the view that impact investment could be a natural complement to the foundation’s shareholder advocacy work and would align with the foundation’s mission, vision, and culture.

Armed with these insights, Pomares and his team then prepared reports calling out areas where interviewees were already in alignment, where they differed, and what issues were most ripe for additional learning. Pomares also teed up conversations with the leaders of foundations in the vanguard of impact investing, including the Rockefeller Brothers Fund and McKnight Foundation. These conversations allowed the trustees and Investment Committee members to engage with peers to understand what impact investment looked like in real life.

The Devil in the Details

When Ruth Cummings convened the trustees with her Lech Lecha invocation, all of the trustees felt that Sonen had done a great job of answering their questions and giving them the confidence to cast a “yes” vote. The reality of the challenges ahead of them sunk in soon after they cast their votes.

The Board had answered first-order questions (“Should we become serious impact investors, and if so, should we go all in?”), but it quickly became clear that the next-order questions were “almost endless,” in the words of Jaimie Mayer, Board chair. “At first, everyone was caught up in excitement,” says Rey Ramsey. “Then we had to figure out exactly what we had all agreed to. Transitioning to impact work affects everything that you do, every decision that you make.”

Weeks after the vote, Bob Bancroft joined the foundation as its new vice president of finance. He quickly became a key player in implementing their decision to align all investments with the foundation’s mission. “Bob’s leadership cannot be overestimated,” says Meredith Heimburger, the director of impact at GEM. “He’s an incredible barrier crosser. I’ve learned so much watching him in that role.”

Bancroft, a thoughtful, soft-spoken man who had spent a decade honing his craft at the Jack Kent Cooke Foundation, admits he had a steep learning curve on impact investments when he joined the foundation; the Cooke Foundation was a traditional investor. Yet, the challenges appealed to both his head and heart.

While Bancroft may appear to be a chief financial officer out of central casting, he did not grow up a child of privilege. When he was only a few months old, his father died, leaving the family in difficult financial straits. “The experience of being financially broken, and the struggle to put the pieces back together, is part of who I am. It animates my belief that all people should have the opportunity to thrive.”

Over the next three years, Bancroft helped the foundation navigate not just one impact investment transition but three.

SCREEN TIME

The first transition was using the foundation’s new investment values statement to screen the portfolio for investments that had to go. In the words of Ramsey, “We had to find out exactly what we had in our portfolio and get rid of the bad stuff.”

In many cases, it was easy to determine what the “bad stuff” was but not always. For example, one of the foundation’s earliest moves was to shift some of its fixed-income portfolio to a socially responsible manager. There was a catch: a tiny portion of the fund was invested in several “best in class” fossil fuel companies. “It was a corner case for us,” explains John Levy. “It tested our thinking and led us to identify several qualitative factors for assessing potential investments: intentionality, directionality, and materiality.”

“ESG data give you a static snapshot. They don’t tell you anything about how fund managers will make decisions tomorrow.”

Then there was the challenge of timing. The foundation could not liquidate all legacy investments quickly. Jaimie Mayer acknowledges that the pace frustrated her. She felt pressure to follow the Board’s bold announcement with concrete action, even though she fully understood the Board’s fiduciary obligation to unwind responsibly. “We were at every conference known to man talking about our decision, but after a while, it started to feel so empty.”

The methodical pace of unwinding and the communications challenges that flowed from it were far from the biggest problems Bancroft and the Board faced. More importantly, they came to see that ESG screening was too limited. “ESG data give you a static snapshot. They don’t tell you anything about how fund managers will make decisions tomorrow,” Bancroft says. To illustrate his point, Bancroft points to an analysis of a particular hedge fund that scored well according to standard ESG metrics. At that particular moment, it didn’t have any fossil fuels in the portfolio, but the firm was not obligated to avoid fossil fuels if a good opportunity presented itself. “We needed to understand more about the managers’ intentions,” Bancroft says.

The ABCs of Measuring Impact

That realization led Bancroft to initiate the foundation’s second transition, from ESG screening to a more sophisticated system of assessing investments’ positive and negative impacts.

GEM brought in Brian Trelstad, a veteran impact investor, to help. Trelstad was one of the architects of the Impact Management Project (IMP), an open-source project facilitated by Bridges Fund Management and created with input from more than 2,000 impact investment practitioners and standard-setting bodies. Over the next nine months, GEM and the Bridges team applied the IMP framework to every investment in GEM’s $10 billion portfolio — a massive undertaking that required 1,200 hours and 14,000 points of data.

Lisa Hall, an impact investment leader and one of the key members of the foundation’s Investment Committee, had co-authored the report, More than Measurement, that would eventually inspire the creation of the IMP. She recognized its strength in theory and was excited for GEM to apply it in practice; the framework would be applied to a large, multi-asset-class portfolio for the first time. “When Lisa suggested we look at IMP, I was immediately struck by its clarity,” Bancroft recalls. “IMP looks at impact across multiple stakeholders and along two dimensions: the impact of the fund and the fund manager’s contribution to the impact. This got to the question of intentionality we’d been struggling with.”

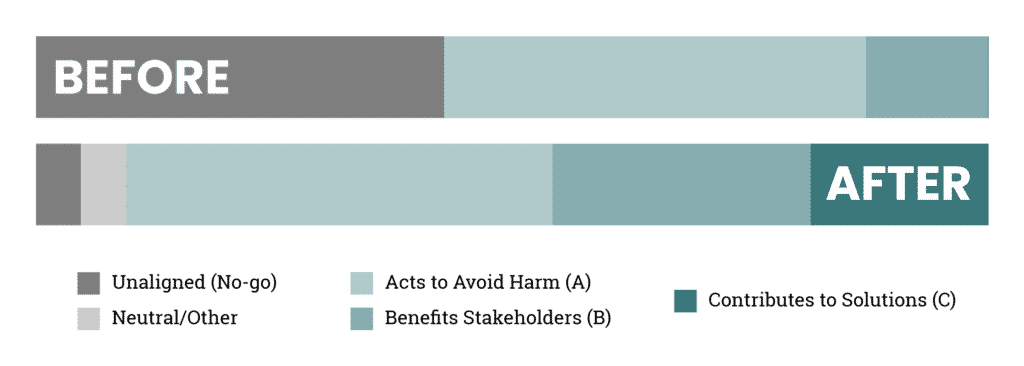

It was implementing the IMP system that allowed GEM to break down the foundation’s current and potential investments into four categories:

- No-go investments: those that do not act to avoid harm

- Category A: those that work to avoid harm to stakeholders

- Category B: those that seek to benefit stakeholders

- Category C: those that aim to change the world for the better by contributing to solving some of the world’s greatest problems

When the foundation’s trustees made their mission-alignment commitment, nearly half of their portfolio was out of alignment with the mission (no-go investments), and only 0.1 percent were contributing to solutions (category C).

Today, the portfolio looks very different. Only 5 percent is out of alignment with the mission (no-go); most of these investments are illiquid assets that the foundation will unwind over the next five to ten years. The foundation has more than doubled its investments that seek to benefit stakeholders (category B) — from 13 to 27 percent. Even more significant, it has increased investments in contributing to solutions (category C) from 0.1 percent to 19 percent. These category C investments include L+M Development (an affordable housing developer and manager), Precursor Ventures (a Black-owned firm with a focus on diverse entrepreneurs), BBG Ventures (a women-led firm with a focus on supporting diverse women entrepreneurs), and a fund investing in the largest battery-storage project in the world.

GEM’s work with Trelstad and IMP had ripple effects beyond the foundation. GEM implemented the IMP framework across all of its clients. Honoring the open-source nature of IMP’s framework, the GEM team freely shares their insights with other firms — even competitors. Across all of their clients, including traditional investors, GEM has collectively made $1.5 billion in new impact investments and commitments. “We believe that impact investing is critical to the future of our industry,” GEM’s Heimburger says.

Focusing on Racial Equity

While the work with GEM and IMP progressed, Ramsey and Bancroft triggered the third transition. It started with a painful meeting in August 2018.

At GEM’s offices in Charlotte, North Carolina, the GEM team shared with the foundation’s Investment Committee its decision to decline an investment in a fund led by a woman of color. GEM’s rationale seemed reasonable and logical, but it did not sit well with the foundation’s team. The foundation saw a significant impact and financial potential in the fund, and they were deeply impressed with the fund’s manager. Bancroft was the first to speak up. He asked, “How can we expect to solve these problems by following the same playbook that helped create them in the first place?” He was referring to entrenched barriers that have perpetuated an investment world managed almost entirely by white men.

“How can we expect to solve these problems by following the same playbook that helped create them in the first place?”

Ramsey, a Black man, felt the same way. “I’ve faced these challenges my whole life, professionally and personally,” Ramsey says. “I was grateful that Bob was asking those questions. For once, I didn’t have to be the one to do it.” Later that day, Ramsey opened up to Bancroft, whom he did not yet know well. Ramsey shared that in the early 1960s, his welder father and hospital-worker mother moved the family to a town in New Jersey, where they became the only Black family. The day after their move, local members of the Klu Klux Klan spray-painted a hateful “greeting” near the Ramseys’ house. His Catholic elementary school should have been a refuge, but it became a crucible of bullying, and not just by jeering classmates; the ringleader was his third-grade teacher. Ramsey overcame many such challenges and would go on to build an impressive career, with leadership roles spanning the public, private, and philanthropic sectors. But those memories of overt racism and exclusion reverberate to this day.

The conversation led Bancroft and Ramsey to commit to doing their part to dismantle such barriers and shift capital to funds and communities that had been underrepresented in the sector for far too long. Over the next two years, the foundation would follow a model that had worked well in the past: leaning into tough conversations, gathering data, and listening to those who had wrestled with the issues before.

GEM’s team had also left the August meeting with a sense of commitment. They began to incorporate questions around diversity, equity, and inclusion into their standard due-diligence questionnaire and began to expand their networks. Within a year, they had grown their pipeline of potential investments dramatically, expanding tenfold the number of funds led by women and/or people of color.

The foundation’s Investment Committee heard from peers and outside experts about the obstacles faced by Black and Brown fund managers, both emerging and established. In August 2020, in the wake of George Floyd’s murder and the uprisings that followed, the committee adopted an equity lens framework that laid out four guiding principles and a set of commitments based on the recommendations of the Association of Black Foundation Executives (See Appendix Two).

By that time, GEM had completed a project to study best practices and address racial and social equity in the portfolio, including a report with metrics for diversity, social equity, and racial equity. As of December 2020, 28 percent of the foundation’s portfolio was managed by funds that are majority-owned by women and/or people of color, but only 9 percent had applied a racial equity lens to the underlying investment decisions.

For Ramsey and Bancroft, these metrics were signs of progress and indicators that much remained to be done. The two express regret that they didn’t identify the need to be explicit about applying a racial equity lens sooner. “The Investment Committee approved the equity framework almost three years after our Board fully committed to mission-aligned investing,” Bancroft says. “This would have been first if we could do it all over again.”

As of this writing, Bancroft, Ramsey, and the foundation’s Investment Committee are still in the process of implementing the equity lens framework. The third transition is not complete.

CONCLUSION

In addition to implementing the new racial equity lens, the foundation will face many key decisions in the years ahead, including the selection of a new president and CEO. High on the incoming leader’s action list will be determining what organizational changes might be necessary to ensure the foundation has all the right skill sets covered and can build more connective tissue between the investment team and the program team.

“Investments alone will not repair what’s economically broken in our society.”

Jaimie Mayer is acutely focused on maximizing cross-pollination in the foundation — so that the foundation’s investments amplify its programs and vice versa. Ideally, she would like the new president and CEO to hire staff with both sets of experiences, but she acknowledges that this will be tricky. “Ninety-nine percent of foundations are not operating this way, so there aren’t a lot of people out there who understand both cultures. We’re looking for unicorns.”

After the foundation wrestles with these important organizational issues, Mayer will ask the Board a literally existential question: Should the foundation remain a perpetual foundation, or should it be willing to spend down its endowment over time? “I’m not fully in the perpetuity camp anymore,” Mayer says. “It’s not that I would like to sunset, but I also don’t want to sit on these resources when the world is burning. I’m willing to put everything on the table in pursuit of greater impact.”

Mayer intends to center the Board’s June 2022 retreat on perpetuity versus the urgency of now, a theme that operates at the intersection of the foundation’s investing and spending policies, and one that touches on the very heart of its social justice mission. When she opens that retreat, she will not use the Lech Lecha portion of the Torah. But she may remind her fellow trustees of Abraham’s willingness to break from his forebears’ traditions in pursuit of his own courageous transformation.

Mayer and the other trustees recognize that their investments alone will not repair what’s economically broken in our society. Inspired by Lech Lecha, they will keep asking themselves what more they can do to “go to the place that is your own” and bend the arc of their philanthropic journey toward justice.

Lowell Weiss, a former Atlantic Monthly editor and White House speechwriter for President Bill Clinton, is the president of Cascade Philanthropy Advisors.