We were at a crossroads two years into our journey to implement a mission-aligned investing strategy across the entire endowment. We made significant progress, yet we remained restless. We wanted to understand the extent to which our social justice mission could be authentically reflected in every facet of our investing. We saw an opportunity to engage leading OCIOs to help find the answers, and we retained Frontline Solutions to conduct the research.

We would like to express deep gratitude to the eighteen firms who took considerable time and effort to participate in our process. We have listed each of them in the acknowledgments section of the report.

The Power of the OCIO

We felt it was important to highlight the significance of the OCIO model in the philanthropic sector before presenting our findings. The model emerged to satisfy the need for a total portfolio management solution, which bridges the gap between investment consulting and asset management. A key facet of this model is the notion of “full discretion,” meaning that the OCIO has the authority and the power to allocate capital on behalf of the asset owner. In essence, the OCIO acts as an intermediary between the asset owner and the fund managers within the portfolio.

According to Federal Reserve estimates, private foundations in the US held $968 billion in total assets as of the first quarter of 2020, up from $573 billion a decade ago and $459 billion a decade prior. The OCIO model’s adoption has been on an upward trajectory over the last decade, surging by 37 percent annually since the Great Financial Crisis. This growth has been fueled especially by small- and medium-sized institutions, who seek a sophisticated approach to investment management but lack the scale to viably recruit an in-house team. In 2018, more than 90 percent of private foundations surveyed used some form of investment advisors to facilitate manager selection, and 30 percent of foundations surveyed utilized OCIO services, per the Council on Foundations and Commonfund.

“We must clearly identify and address the transfer of economic power through our investments to better align our investments with our mission.“

These firms are gatekeepers to the vast majority of philanthropic capital. Such capital can confer power and self-determination or, if not equitably allocated, cause deep and lasting harm. Recognizing this, we made an understanding of these dynamics a key part of our inquiry. We must clearly identify and address the transfer of economic power through our investments to better align our investments with our mission.

METHODOLOGY

We conducted our research in two phases. In phase one, we cast a wide net across the OCIO space to ensure a broad sampling of styles and approaches to mission-aligned investing. In addition to a preliminary universe of OCIOs, we leveraged both traditional industry resources, such as Ai-CIO and Skorina, and less traditional ones, such as the Diverse Asset Managers Initiative, to produce a broad and representative sampling of this dynamic market.

Casting a Wide Net

We identified twenty-five leading firms using this ranking system along with other insights gleaned from the first phase. We then invited them to participate in the second phase of our research through a confidential request for information (RFI). Eighteen of the firms chose to participate. We did not set out to create a definitive ranking for others. Institutions with other priorities may have ranked these leading firms differently.

We augmented the phase two RFI with an optional Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Addendum (Appendix Three) because we were especially interested in understanding how OCIOs thought about issues of diversity, equity, and inclusion. The document requested transparency around a variety of metrics, including internal DEI practices, staff diversity statistics, the number of diverse-led funds researched versus placed in client portfolios, and any improvements that the firm had made toward inclusive sourcing and engagement. Our intention was also to signal that these firms should anticipate similar requests from clients and prospects in the future. In the end, half of the respondents completed the Addendum, although many were not able to provide complete data.

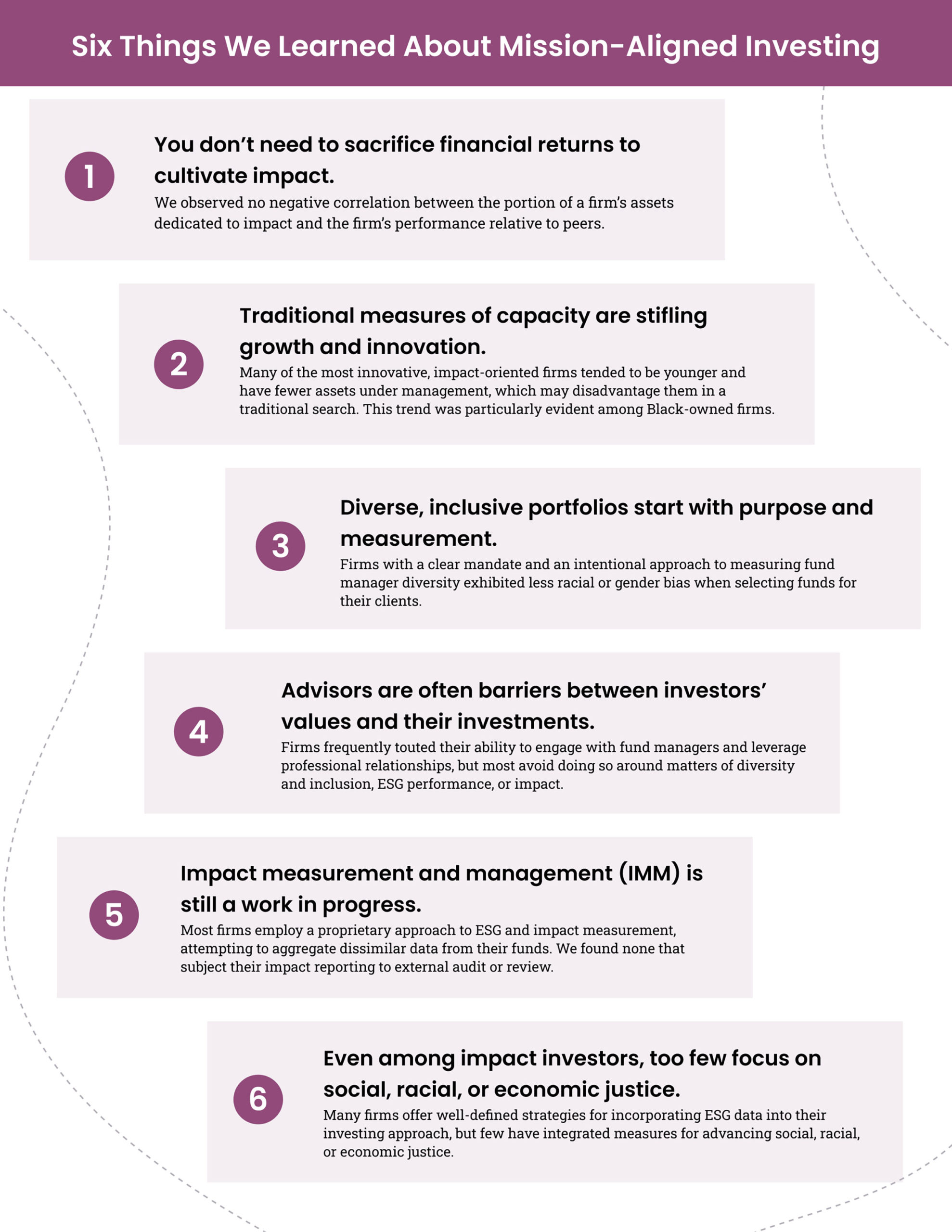

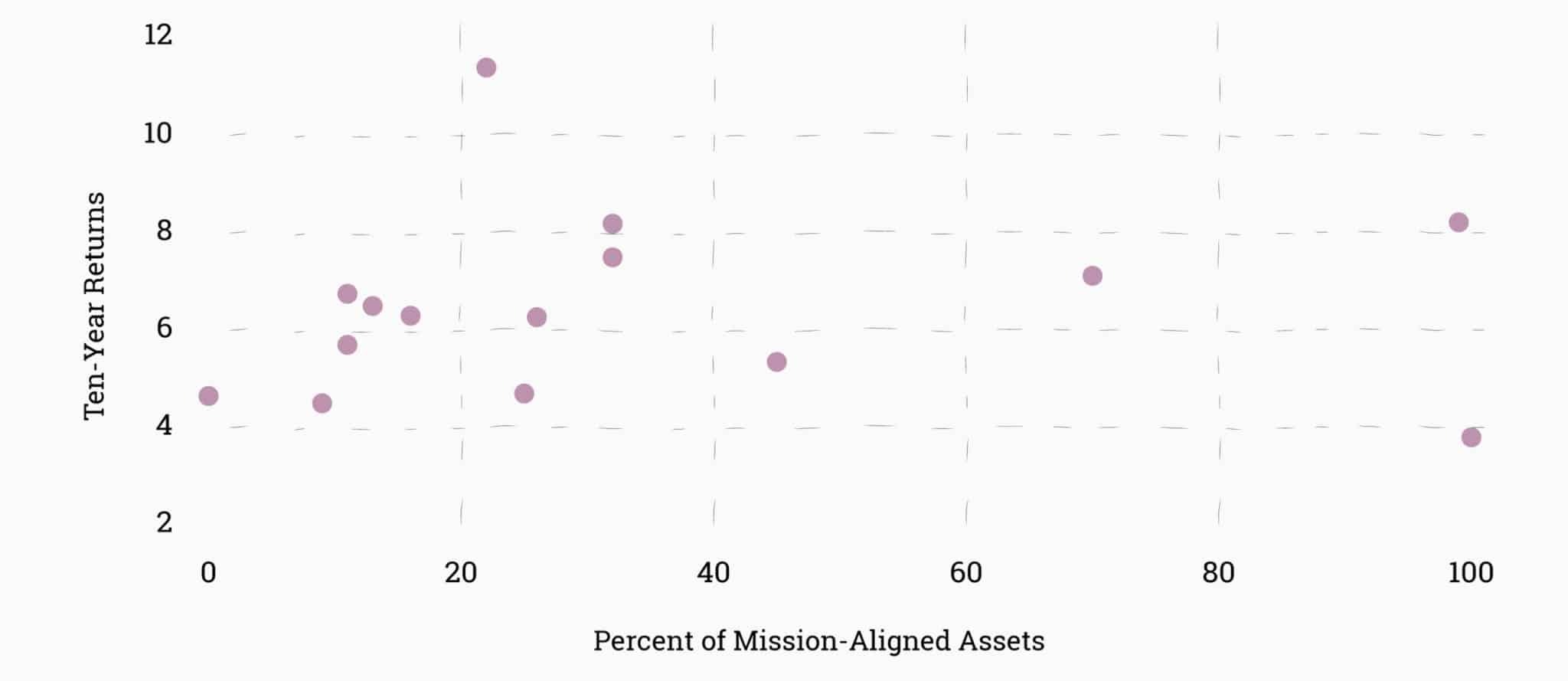

Finding One: You don’t need to sacrifice financial returns to cultivate impact

A growing interest in mission-aligned investing is often met with concerns about the potential for increased risk or dampened returns. Yet, we observed no negative correlation between the portion of a firm’s assets dedicated to impact and its financial performance from our analysis of the RFI responses. On the contrary, we found that institutions working with an OCIO are not required to sacrifice financial returns to apply a mission-aligned approach to their investing. This finding builds on empirical research that concluded that portfolios screened for ESG performance do not negatively impact returns, nor do they experience additional volatility.

Performance vs. Percent of Mission-Aligned Assets

Sixty-three percent of the 115 firms that we reviewed incorporated some form of ESG factors into their assessment of managers and their underlying investments. Fifty-six percent featured SRI and/or impact prominently in their marketing. Therefore, we consider any firm that does not offer robust ESG and impact integration to be lagging in the market.

We observed two distinct approaches to constructing mission-aligned portfolios, which we describe below.

- Traditional, with impact as a lens. This approach first identified the financial needs of a client to determine asset class allocation, building the portfolio in a conventional manner. Products were often: identified as a subset from an existing platform; screened based on ESG, responsibility, diversity, and/or impact; and then placed within the predetermined allocations. We observed this to be the most common approach. These firms treated impact as an add-on to the existing model rather than a fundamental shift in thinking. We believe this approach can contribute to achieving mission alignment, but it may be less likely to maximize impact.

- Impact-first, with impact as alpha. This approach first considered the pressing, mission-relevant challenges and opportunities that may be suitable for private-market solutions. It then worked backward to construct a portfolio that meets their clients’ financial goals. These investors typically identified social and environmental impacts as hidden sources of alpha. Essential to this approach was an understanding that there was unrecognized value in investments that meet impact goals, and, therefore, impact goals should lead the asset allocation process. For the purpose of our research, we considered a firm to be “impact-first” if it had at least 70 percent of its assets under management in impact or other mission-aligned strategies. We saw few firms pursuing this model.

In terms of structure, we observed that the majority of firms treat mission-aligned investing as a line of business catering to a specific client segment. In such cases, a relatively small team was responsible for the implementation and execution of a firm’s mission-aligned investing. Rarely was it the sole focus or integrated across the entirety of a firm’s infrastructure (i.e., sourcing, investment research, execution, operations). While this may be an appropriate entry point for traditional firms, we would encourage them to adopt a more integrated approach and utilize these tools across their entire platforms.

Many Investment Committee discussions about mission-aligned investing are cut short by the falsehood that it would come at the cost of performance. We believe that employing an impact-first approach that uses impact alpha drivers allows any mission-driven asset owner to optimize for both financial and mission returns. The data are clear that mission-driven institutions, such as private foundations, do not need to sacrifice financial returns for mission alignment.

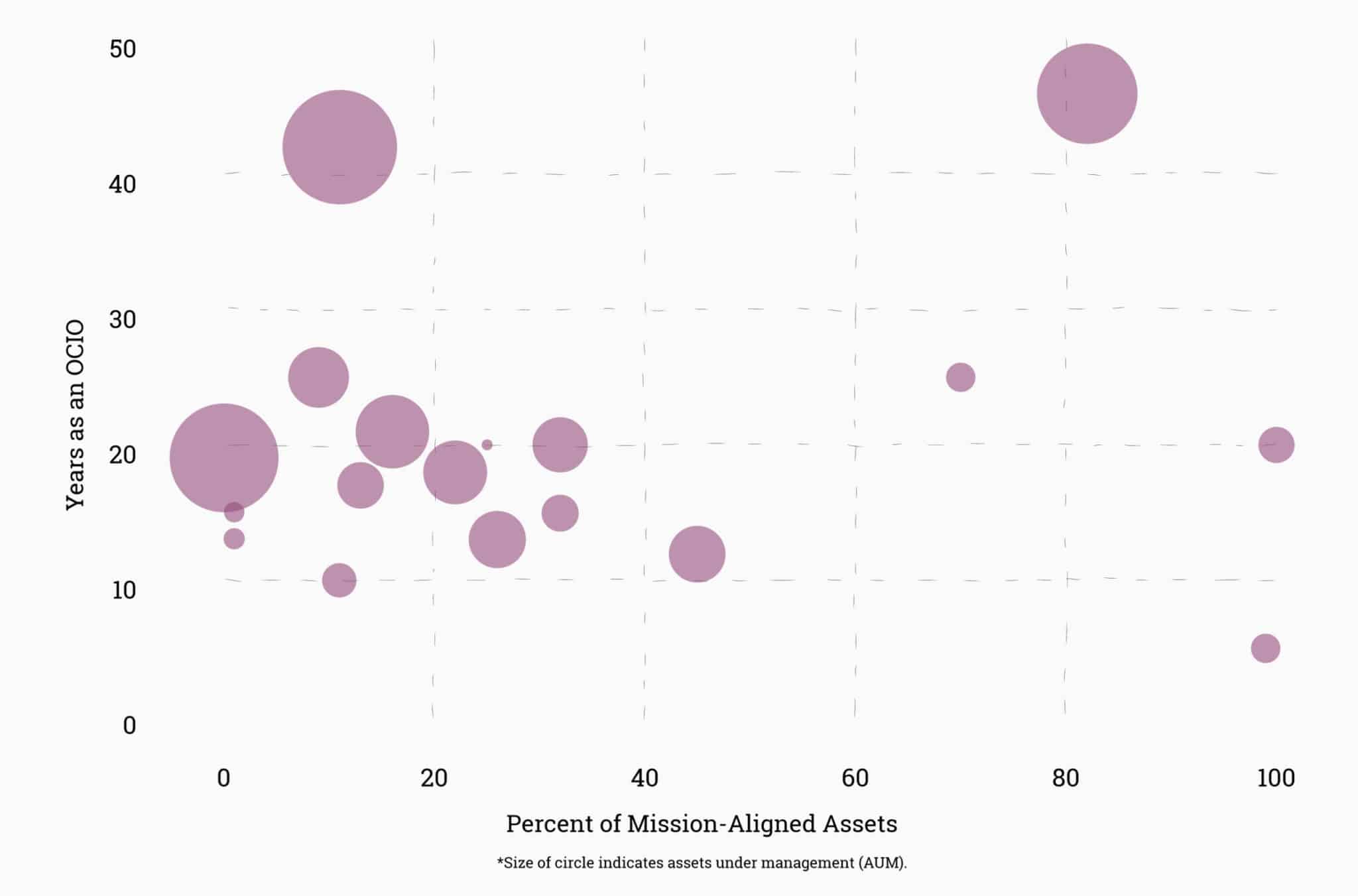

Finding Two: Traditional measures of capacity are stifling growth and innovation

The few firms that took a fully integrated, impact-first approach tended to be younger, had fewer assets under management (AUM), and were generally launched explicitly to pursue impact. Nearly all were launched in the past twenty years, and most were created within the past decade. The firms themselves tended to have shorter track records, even while the founders and leaders carried considerable experience. This was especially true for firms led by people of color and/or women. In some cases, these firms tended to focus on a subset of asset classes and/or geographical sectors, perhaps because of having smaller teams.

“Mission-aligned investors will need courage and creativity to find ways to support these emerging impact leaders and benefit from the work they are doing.”

These characteristics may disadvantage these firms in traditional searches and create barriers to their adoption among larger institutional clients. A perceived lack of client management experience and/or full asset class diversification — even when there is risk-adjusted outperformance — can result in innovative OCIOs being screened out of search processes prematurely, which has the consequence of keeping them artificially small. Few endowments or foundations want to be the first or the only large asset owner being managed by an advisor, leading to unspoken but real impediments. Thus, we see a chasm between those firms already operating at scale and those seeking to achieve it. Mission-aligned investors will need courage and creativity to find ways to support these emerging impact leaders and benefit from the work they are doing.

Finding Three: Diverse, inclusive portfolios start with purpose and measurement

We are committed to promoting diversity, equity, and inclusion in every aspect of our institution — and our investing process can be no exception. We seek an inclusive and antiracist approach that promotes diversity and inclusivity throughout the investment value chain, starting with the OCIO or advisor, continuing with the portfolio fund managers, and resulting in investments in enterprises that integrate a justice and equity lens to have a positive impact on the communities we serve.

Investment Value Chain

In addition to a moral argument, asset owners have a well-founded business case to promote diversity, equity, and inclusion. As highlighted in recent McKinsey research, firm profitability, growth, and job satisfaction all positively correlate with higher levels of diversity and inclusivity. Specific to investment management, we also know that diverse-led private equity funds continue to outperform the Burgiss Median Quartile in 79 percent of the vintage years studied, according to NAIC. However, despite consistently delivering strong returns, diverse- and women-owned firms collectively manage only 1.3 percent of the industry’s $69 trillion in assets under management — clear evidence of the biases and structural barriers present in the sector.

As a mission-driven foundation that prioritizes racial justice, we wanted to know what OCIOs were doing to address this disparity and how investors might benefit by tapping into these vast reserves of overlooked or undervalued talent. Accordingly, we asked these firms to tell us what an equitable and inclusive investment portfolio would look like, what barriers were impeding them from making more investments in diverse-led funds, what types of diversity and inclusion data they were collecting, how they were using it, and to what effect.

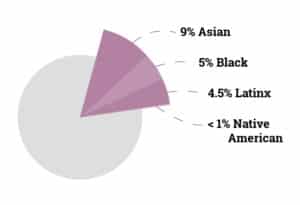

Unfortunately, the responses we received indicated a collective weakness in this area. This weakness manifested as underdeveloped or absent processes relating to hiring and advancing a diverse workforce within the firms, making investments into diverse-led funds, and/or investing in products that incorporate a perspective on racial, gender, ethnic, and/or economic justice. For example, only five of the 115 firms in our initial survey explicitly addressed the diversity of fund managers within their portfolios, which we considered a significant oversight and shortcoming. Only thirty of the 707 senior leaders across these same firms were Black or Latinx.

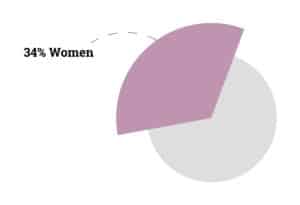

Total Staff Diversity Among OCIOs

Some respondents attributed these outcomes to a dearth of talent or investment opportunities in the pipeline. While we think efforts to improve the pipeline can be helpful, we disagree with the assertion that the talent pipeline is the limiting factor. We believe our position is well-supported by the facts, including a recent study from Stanford SPARQ, Illumen Capital, and the Global Projects Center, which surfaced how racial blind spots interfere with investors’ judgment in the absence of an intentional focus on diversity.

Yet, there is reason to be hopeful. Through our analysis, we identified several factors that appear to reduce bias and strengthen the investing process, such as:

- A clear mandate, including internal audits and support from senior executives

- Diverse staff, particularly at the leadership and investment committee levels

- An intentional approach to collecting and measuring diversity and inclusion data throughout the investing pipeline

We observed that firms that adopt one or more of these practices exhibit demonstrably less bias in selecting funds for their clients, thereby creating an opportunity to outperform by selecting underestimated managers. Measurement was the most clearly correlated to bias reduction, reinforcing our belief that institutional barriers and personal biases are the primary impediments to sourcing and placing more capital with diverse-led funds.

Finding Four: Advisors are often barriers between investors’ values and their investments

Since 2002, we have sought to leverage our standing as a shareholder to advance ESG issues at some of the largest, publicly traded companies in the US. For almost two decades, we have used this form of shareholder engagement – filing shareholder proposals and voting our proxies intentionally – to shine a light on harmful practices and change corporate behavior. For example, our recent engagement with Discovery Communication spanned several years and resulted in their Board’s commitment to instruct any external partners identifying Board of Directors candidates to include diverse candidates in their list. Discovery added Robert L. Johnson, founder of Black Entertainment Television (BET), to its Board of Directors following the conclusion of our engagement.

There is a catch: we can only pursue this line of engagement when we own shares of stock in the companies. The vast majority of our endowment is invested in commingled funds like most of our peers. In that case, the funds are considered the shareholders and thus the parties with the power to vote proxies or file proposals. Therefore, we were keenly interested in knowing how OCIOs are working with fund managers to monitor and/or influence this important activity.

“We see clear evidence that OCIOs have the power to extend that engagement to include issues of diversity and inclusion, ESG, and impact. The motivation or the will to do it is what appears to be lacking.”

Unfortunately, we found nearly all OCIOs are hands-off about this. The few exceptions tended to partner with outside organizations, like As You Sow, for guidance. This approach is certainly a step in the right direction, but it may not always fully represent asset owners’ priorities. Only one OCIO articulated a clear vision and mandate around shareholder engagement as a tool for impact. Despite this, nearly all respondents touted their ability to engage fund managers and leverage closely held relationships in ways that enhance performance for their clients. Thus, we see clear evidence that OCIOs have the power to extend that engagement to include issues of diversity and inclusion, ESG, and impact. The motivation or the will to do it is what appears to be lacking.

Most OCIOs instead tend to guard their relationships with fund managers and minimize contact with clients. This creates certain efficiencies for the intermediaries, but it can also create barriers that erode or prevent the transmission of values between the asset owner (the client) and those making decisions across the portfolio (the fund managers). We believe mission-driven institutions need to reexamine this arrangement and establish new ground rules, new forums, and new modes of access to ensure the transmission of values and priorities is direct and strong.

Finding Five: Impact measurement and management (IMM) is still a work in progress

Most firms employ a proprietary impact measurement system, which is often positioned as a firm’s unique advantage. Most have also tied their system to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals to some extent, but only a few fully integrate more widely accepted ESG or impact measurement platforms, such as the SASB Materiality Map, IRIS+, GIIRS / B-Analytics, or the Impact Management Project. We worry that the proliferation of closed-box, proprietary systems among asset allocators creates barriers for new investors, and we believe it may undermine credibility and accountability for the impact investing movement. We encourage investors and advisors to leverage existing tools and frameworks to the greatest extent possible and contribute to these projects rather than creating entirely new systems.

In addition to impact measurement, we observed a range of practices around identifying and assessing impact risk. Some firms pursued a traditional approach to underwriting, centered on financial risk. Others sought investments where the impact and financial theses were sufficiently co-dependent so that one was not likely to happen without the other. Only a few firms appeared to rigorously examine each investment’s impact thesis and consider the likelihood that the desired impact(s) may or may not occur. We believe such rigor will be required to properly optimize the portfolio’s risk, return, and impact characteristics.

“We conclude that there is a significant opportunity to improve the rigor and transparency of impact reporting by incorporating reliable third-party data and audits.”

Lastly, we found that OCIOs are largely reliant on self-reported data provided by the funds. To further complicate matters, these data come in all shapes and sizes, and there are no agreed-upon standards for how they should be aggregated. This can significantly impair the utility of whichever tools OCIOs use to report impact performance to their clients.We conclude that there is a significant opportunity to improve the rigor and transparency of impact reporting by incorporating reliable third-party data and audits. After all, we depend on financial audits as a standard practice that strengthens our capital markets. We imagine that impact audits will eventually have the same degree of acceptance or perhaps become integrated with financial audits.

We also observed the following best practices:

- Leverage and contribute to existing frameworks and systems that measure impact

- Establish clear and appropriate benchmarks for impact performance

- Incorporate reliable third-party research and listings, such as the Carbon Disclosure Project’s A-List, or the Adasina’s Racial Justice Exclusion List

- Engage an assessor experienced with sourcing diverse-led funds, such as the Diverse Asset Managers Initiative, to serve as a credible partner to develop and implement a DEI audit and other tools to reduce bias

- Engage a third party, such as Trucost, to conduct an impact audit to evaluate the appropriateness of reported data around ESG performance

Finding Six: Even among impact investors, too few focus on social, racial, or economic justice

In this report, we offered an assessment of the state of play among mission-aligned investors and advisors. We presented our findings as a snapshot of a field that is undergoing rapid change. We indicated what is possible today, what we saw as best practices, and where we found gaps. This research eventually led to what we see as the impact frontier — investments that integrate and directly advance social, racial, or economic justice. We found the possibilities compelling, but such investments remain uncommon and elusive.

Consider, for example, environmental impact. This topic was widely addressed by the respondents, many of whom provided a clear analysis of how to measure the impact that companies have on climate change and what investments are needed to transition to a clean economy. Few appeared to be thinking about how these challenges and opportunities intersect with issues of racial or economic justice. In the US, our most vulnerable communities — including communities of color and other disinvested communities — have borne a disproportionate share of corporate pollution for decades. Without an explicit focus on justice, these same communities will likely be excluded from the economic benefits of a clean energy transition or bear the worst effects of climate change.

We see the potential for a new, more enlightened capitalism, where economically and environmentally restorative investments are made to empower those communities most harmed by such behaviors. After a global pandemic laid bare the inequities of our existing systems while also reminding us of our interdependence, we have never felt greater urgency. If mission-aligned investing is to realize its potential as a tool for achieving systems change — if we are to create real and lasting impact — then we must test our social justice thesis at each step of the investing process. That requires us to address power. All investments impact and confer economic power, but the tools and intentionality to manage this at scale have lagged. Therefore, we suggest the following analysis be incorporated into the evaluation of any potential investment:

- Who controls the resources?

- How are decisions made?

- Where is economic power built?

We believe such an analysis will be additive to investment performance over time, which is consistent with our previous assertions. We see proximity to community and diversity of lived experience as new sources of alpha, because they can overcome blind spots and spur innovation.They expand the aperture of our thinking, and they will enable investors to identify the next wave of breakthrough and economically transformative opportunities. Private capital can be recruited as a force for good. We get there by integrating a social justice thesis throughout our investment decisions.